A Necessary Foreword

In due course I attended Nanpantan infants school where Miss Barron's passing out test required perfect knowledge of the times tables up to twelve, a standard not even attempted after these 68 years of advanced educational theory. At Shelthorpe Junior school this good start enabled me to bypass the second year. Hence I passed the "eleven plus" aged 10 and was presented with a choice of senior schools. While girls went to the High School, boys could opt for either the Grammar School or Loughborough College School. Quite naturally it was the latter for me as my elder brother already went there and the Grammar school was deemed to be "far too posh".

The LCS was a prefabricated School in several senses. It had been conjured up in the thirties to serve as a feeder for Loughborough College which provided higher education in engineering science and training for Physical Exercise teachers. The main part of the school consisted of a dozen classroom huts with a spinal corridor squashed into a corner of the College premises off a back street of the town. The tiny playground consisted of asphalt areas on top of the double decker air raid shelter. The School had no assembly hall so we had a daily short walk to the nearby Methodist Church to sing our hymn and recite a prayer and then to assimilate the notices usually delivered by the Head Master "Alf","The Boss" Eggington. However, what this seemingly deficient school did provide was the use of all the College's splendid facilities, hence Woodwork and Metalwork were undertaken in well equipped modern workshops and PE in a most wonderful gymnasium. We did PE in nothing but white shorts as plimsolls were not deemed necessary on such perfect teak flooring. Afterwards the sweating herd would be directed en naked masse through the steaming showers.

However there was an additional and more spacious part to this meagre campus. The College had extensive playing fields half a mile away with literally dozens of pitches and tennis courts together with more gymnasiums, an athletics arena and both indoor and outdoor swimming pools. Set amongst these were the College's two halls of residence, Rutland and Hazlerigg, and for the school on a raised area nearby, were four prefabricated buildings providing classrooms, the art room, biology and physics labs. The College sports facilities were of such a high standard that in 1948 they were used for training by many Olympic athletes, both British and foreign.

For two years I happily oscillated between the two separate sections of the school as necessary to receive my education, but then things changed. "The Brush " decided to do away with its coach body building division and my father, by then the Timber Yard foreman, was made redundant. My mother had suffered our primitive accommodation for ten arduous years and pleaded for better. My father, then at the awkward age of 49 considered himself lucky to obtain a new job as a wood machinist for St. John's College in Oxford, especially as this offered a tied three bedroomed "cottage" with all mod cons. Accordingly we moved south in the summer of 1950 after my brother had matriculated at the College. We found that Oxford had a technical school in the Cowley Road and I assumed that was where I would be attending but as we lived in the village of Kennington and hence just in Berkshire, it was not to be. When the letter arrived from the Berkshire LEA there was no choice offered, I was to attend the Grammar School, six miles away in Abingdon.

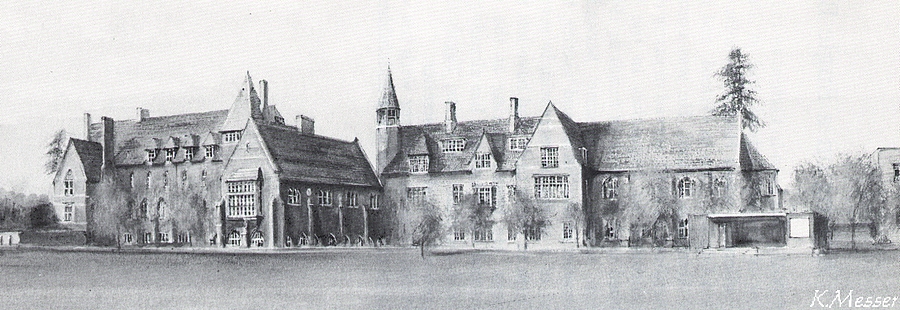

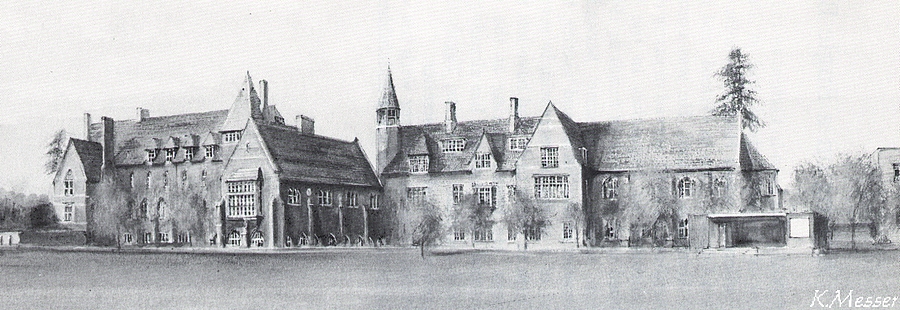

A letter from the school summoned me for interview and my father and I were duly impressed when we saw the School for the first time as it was so completely different to what I had been accustomed. The old building looked really beautiful, benignly sitting in the sun behind the cricket field, being constructed in red brick and obviously extended in stages with the work being done many years ago, apart that is from one flat roofed rectangular block to the right which was very new indeed.

With my twelve year old knees trembling, Headmaster James Cobban, who enunciated in the clipped BBC manner, no doubt winced when he heard the rural Leicestershire tones of my presumably satisfactory responses to his few questions - think unreconstructed Gary Lineker and you'll get the idea. After a cursory inspection of my College report, he happily accepted the Direct Grant, thereby becoming obliged to take the associated small apprehensive pleb quivering before him, saying that he would not require him to commence Greek but that he would have to commence Latin. On the way out, the secretary handed us the official clothing needs list, most of which had to be obtained from Abingdon's sole smart gents outfitters. Back home, "Six pairs of underpants?" gasped my mother, being unable to imagine how more than three were necessary, but then we realised the list was undoubtedly provided to advise the parents of the boarders. However, the cap, tie, two rugby shirts and socks were unavoidable purchases but I feel that it is now safe to reveal that my grey shirts and suit were in fact obtained from the CO-OP. A week before the September term began a bus season ticket arrived from the LEA, this being a great relief to my parents as money was tight, my father's earnings being little better than that of an agricultural worker.

The First Few Days

In the third week of September the dreaded day duly arrived. A boy about my own age in the school uniform boarded my No.14 bus at the far side of Kennington and two more at Radley, but though I looked hopefully at them, none acknowledged me. Deposited outside Abingdon's tiny railway station, as I followed the three others the first boy did enquire if I was "new" but little more was said. We walked briskly along the gated Park road and turned by The Lodge up the gravel drive to the school. In the stone flagged entrance hall, within a seething maelstrom of pupils the first boy said "Find your name in the form lists on that noticebord and it will tell you your form room", which he did himself before quickly disappearing. I found that I was in class 3B which was in the Blacknall room and the form master was a Mr Johnson. All the other boys were speedily dispersing and I could find no school map on display to indicate where I must go. When a loud church-type bell began to toll, panic started to set in.

However, a senior boy appreciating my difficulty and possibly posted there for that very purpose, approached, interrogated me briefly in a decent manner and then hastily conducted me up the worn stone steps of the bell tower. At the second landing he knocked upon and then opened the first door and ushered me into a scenario that could have come from Dickens or the pages of a Greyfriars annual. On a dais in the far corner was a huge desk and chair.  In this sat a large rather forbidding man, his shoulders draped in a shabby black gown. Arranged before him were several rows of ancient communal long desks of the most basic structure - a board to sit on and a much carved and scratched board on which to write. Packed into those were my chattering classmates-to-be who all turned to stare at the new arrival. Mr. Johnson boomed above the din. "Ah. You must be the unknown and missing Adams. So kind of you to join us. Sit there and I will speak to you shortly." His last word of each sentence issued forth on a rising nasal boom. Mr Johnson always boomed like that, but in between his words were very often a quiet mumble.

In this sat a large rather forbidding man, his shoulders draped in a shabby black gown. Arranged before him were several rows of ancient communal long desks of the most basic structure - a board to sit on and a much carved and scratched board on which to write. Packed into those were my chattering classmates-to-be who all turned to stare at the new arrival. Mr. Johnson boomed above the din. "Ah. You must be the unknown and missing Adams. So kind of you to join us. Sit there and I will speak to you shortly." His last word of each sentence issued forth on a rising nasal boom. Mr Johnson always boomed like that, but in between his words were very often a quiet mumble.

The usual start of term things then ensued - the handing out of books, the copying out of the timetable into the special small diary book provided. Eventually Mr Johnson called me forward and in a kindly and confidential less booming fashion quizzed me on my previous schooling. He ended by saying that he was fairly new too and that if I conformed to "our own peculiar ways here" there was no reason I should not do well and be entirely happy in my new situation. He then obliged the next boy to me to "conduct his progress around the school for the next few days if you would be so kind, Walker". This boy was one of those who had boarded the bus at Radley so I felt we already had a modicum of affinity, an idea to which I clung as I so desperately needed a friend, imprisoned as I was in what to me was an utterly alien environment. The form then embarked on its first lesson the nature of which I am unable to recall but it was whatever was Mr Johnsons's speciality.

When the bell signalled the mid morning break all the boys leapt up, took off their jackets and without knowing the purpose, lemming-like I did the same and raced with them down the stairs and out on to the gravelled area in front of the school. There we formed up in rows and under the direction of Mr Coleman, a track suited teacher with a Welsh accent, the whole school of 400 boys commenced a ten minute routine of co-ordinated physical jerks. How this display must have impressed the passers by in Park road! This turned out to be a daily peculiarity and one that I rather enjoyed. After that we retrieved our jackets and sucked down our school milk with Walker thinking he ought to warn me of another peculiarity, the X system of punishment. Prefects could award an X or two for crimes such as being observed not wearing one's cap when walking in the town or indeed, for wearing it when one entered a shop, for running in the corridors or not giving way to teachers or prefects, those sort of things. If one accumulated six Xs against one's name during the term one received three strokes of the cane from Cullen, the head boy. When I gasped at this Walker said that I should think myself lucky as in the former headmaster Mr. Grundy's day the X system did not exist and all the prefects could beat for any infringement. I heard that this term was the start of Mr Cobban's third year as head and that Mr Grundy now lived in a bungalow specially built for him in a corner of the grounds and if he was met walking about the place, which he frequently did, he had to be given an appropriate greeting or woe betide.

When the bell signalled the mid morning break all the boys leapt up, took off their jackets and without knowing the purpose, lemming-like I did the same and raced with them down the stairs and out on to the gravelled area in front of the school. There we formed up in rows and under the direction of Mr Coleman, a track suited teacher with a Welsh accent, the whole school of 400 boys commenced a ten minute routine of co-ordinated physical jerks. How this display must have impressed the passers by in Park road! This turned out to be a daily peculiarity and one that I rather enjoyed. After that we retrieved our jackets and sucked down our school milk with Walker thinking he ought to warn me of another peculiarity, the X system of punishment. Prefects could award an X or two for crimes such as being observed not wearing one's cap when walking in the town or indeed, for wearing it when one entered a shop, for running in the corridors or not giving way to teachers or prefects, those sort of things. If one accumulated six Xs against one's name during the term one received three strokes of the cane from Cullen, the head boy. When I gasped at this Walker said that I should think myself lucky as in the former headmaster Mr. Grundy's day the X system did not exist and all the prefects could beat for any infringement. I heard that this term was the start of Mr Cobban's third year as head and that Mr Grundy now lived in a bungalow specially built for him in a corner of the grounds and if he was met walking about the place, which he frequently did, he had to be given an appropriate greeting or woe betide.

As he chatted Walker showed me the Chapel and the Gym, the first being beautiful but the second an utter disgrace. The chapel was at the end of the second floor corridor and was beautifully appointed. Over the entrance was the organ loft which contained an impressively large instrument. Approached from the lower corridor, beneath the chapel was the Gym. Its floor was not of polished teak but of grimy elm boards worn to such an extent that all the knots protruded as rounded bumps. No chance of being in bare feet there then. There were a few wall bars and the only beam was fixed and mounted across one corner at head height. Not a single rope dangled from the ceiling. Today that Gym would be described as "not fit for purpose." However it was entirely in keeping with the school's primitive classrooms. As indeed was the dayboys' changing room too. Reached from the entrance hall via "The Lats", a partly unroofed area with two rows of cubicles, a row of ancient urinals, and a drinking fountain but no wash basins that I can recall, the Day Boys' changing rooms followed the now expected miserable standard. The two connected shabby small rooms were lined with tiers of battered lockers - for which I was told, padlocks were not allowed. In one corner of one room there was a single shower head which delivered only cold water, and for that reason it was never used.

The chapel was at the end of the second floor corridor and was beautifully appointed. Over the entrance was the organ loft which contained an impressively large instrument. Approached from the lower corridor, beneath the chapel was the Gym. Its floor was not of polished teak but of grimy elm boards worn to such an extent that all the knots protruded as rounded bumps. No chance of being in bare feet there then. There were a few wall bars and the only beam was fixed and mounted across one corner at head height. Not a single rope dangled from the ceiling. Today that Gym would be described as "not fit for purpose." However it was entirely in keeping with the school's primitive classrooms. As indeed was the dayboys' changing room too. Reached from the entrance hall via "The Lats", a partly unroofed area with two rows of cubicles, a row of ancient urinals, and a drinking fountain but no wash basins that I can recall, the Day Boys' changing rooms followed the now expected miserable standard. The two connected shabby small rooms were lined with tiers of battered lockers - for which I was told, padlocks were not allowed. In one corner of one room there was a single shower head which delivered only cold water, and for that reason it was never used.

Eventually twelve thirty arrived and all the boarders descended to the refectory, a large semi-underground room situated below "Big School", these rooms having been built at a right angle to the main construction. The Big School was the original Victorian teaching area and now laid out as two form rooms although there was no division between them. Once again there were rows of simple desks and tall teacher's desks each on a dais, presumably all original equipment as everything was tatty and battered. After half an hour it was our turn to eat. The day boys' food was council supplied, reaching the school in the familiar aluminium insulated containers so as ever it was pretty much inedible. During the remainder of the lunch break period Walker conducted me on the remainder of his tour. We walked around the Wastecourt field, reached through a gate on the other side of a public lane which formed a boundary to the main school area. Returning, we passed a long green Nissen hut belonging to the Combined Cadet Force and then reached the New Science Block. Now here was something bang up to date at last! Three laboratories all brand spanking new and equal to or better than the ones I had been used to at the College.

Rev130111

All text © 2011 D.C.Adams